Anti-Monopoly Bureau of the State Administration for Market Regulation

The year of 2018 has witnessed a significant development of China's anti-monopoly law, marking the 10th anniversary of the commencement of Anti-Monopoly Law (AML), and also the first year of law enforcement after the consolidation of enforcement agencies. Over the past decade, China has experienced astonishing economic growth and become the world’s 2nd largest economy. The implementation of AML has drawn wide attention, making China one of the three major antitrust law jurisdictions on a par with the United States and the European Union. This is not only a result of the rising global status of China’s economy, but also the impact brought by China’s approach to the law and its implications on compliance of enterprises worldwide and the development of China’s market economy.

In this respect, we interviewed the Anti-Monopoly Bureau of the State Administration for Market Regulation (the SAMR) to understand more about the AML’s implementation, and how the newly reformed agency will rationalize its enforcement mechanism, deal with future enforcement work and respond to various competition issues brought by new economies and globalization on the way forward.

AML 10th Anniversary Review

Article 1 of AML provides that this law is enacted “for the purpose of preventing and restraining monopolistic conducts, protecting fair market competition, enhancing economic efficiency, safeguarding the interests of consumers and the interests of the society as a whole, and promoting the healthy development of socialist market economy”. Over the past decade, to what extent AML enforcement has protected fair market competition and the interests of consumers and what difference it has made to China’s economic development? Further elaboration below may present a clearer perspective into the effectiveness and implication of China’s anti-monopoly law enforcement.

Competition Law System

China’s AML was enacted on 30 August 2007 and took effect on 1 August 2008. AML is relatively brief, comprising 57 articles which not only regulate three typical anti-competitive behaviors, namely anti-competitive agreements, abuse of dominant market position and concentration of undertakings, but also forbid conduct that excludes or restricts competition through abuse of administrative power. The latter is against the backdrop that China’s economy is undergoing a structural transition and being considered a prominent characteristic of China’s AML.

Following implementation of AML, the State Council, the State Council’s Anti-Monopoly Commission and the enforcement agencies issued a number of related administrative regulations, guidelines, departmental rules, regulatory documents, procedural guidance and instructions etc. to establish a comprehensive anti-monopoly legal regime which mainly includes the following:

- The State Council issued 1 administrative regulation – Provisions on Thresholds for Prior Notification of Concentrations of Undertakings;

- The Anti-Monopoly Commission of the State Council issued 5 guidelines, including the Guideline for Definition of Relevant Market;

- The agencies issued 12 regulations, 3 regulatory documents, and 10 guidelines and instructions, which include Measures of Review of Undertakings Concentration, Regulations on the Prohibition of Price-related Anti-Competitive Behaviors, and Regulations on the Prohibition of Anti-Competitive Agreements.

Additionally, in 2016 the State Council released its Opinions on Establishing a Fair Competition Review System in the Building of the Market Regime, through which the Fair Competition Review System (FCRS) was launched nationwide to regulate governmental behaviors with a view to preventing policies and measures that exclude or restrict competition from being adopted by the administrations. It is also an effort to remove and abolish regulations and practices that obstruct a unified national market and fair competition.

Constant enhancement of the law and regulation regime with AML at its core facilitates the interpretation of AML and safeguards the institutional basis for law enforcement. Meanwhile, the add-ons also provide more predictability and certainty as regards the application of the law, setting clearer rules for market players.

Enforcement Work

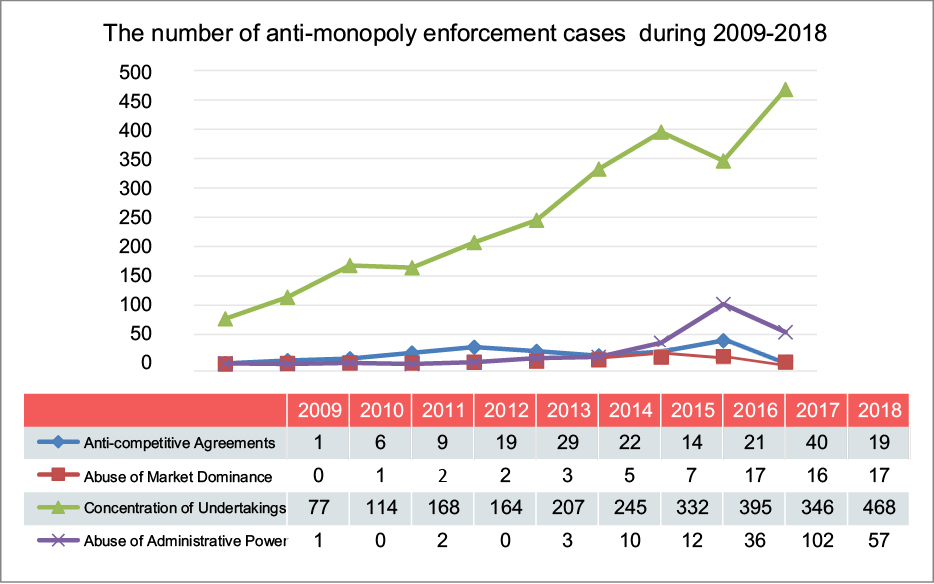

As of the end of December 2018, China’s anti-monopoly enforcement agencies have investigated a total of 172 cases of anti-competitive agreements, such as the cases involving international RORO freight maritime shippers and Shanxi electric power, as well as 58 cases of abuse of market dominance like the Qualcomm case and the Tetra Pak case, with an accumulated penalty of more than RMB 11 billion. The authorities also concluded 2,533 cases on concentration of undertakings with a total transaction amount of over RMB 45 trillion, prohibiting Coca-Cola from acquiring China’s Huiyuan Juice Group Limited and Maersk and others from establishing a network center. They also conditionally approved 39 cases on concentration of undertakings, such as Microsoft’s acquisition of Nokia and Dow’s merger with DuPont. 223 cases with respect to abuse of administrative power were concluded including the case on 12 provincial or municipal governments which abused administrative power to exclude and restrict competition in the electricity supply and distribution network projects for new residential communities. The chart below shows the number of enforcement cases over the years:

The enforcement cases indicated above cover a wide range of industries including semiconductor, telecommunications, transportation, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, paper production, industrial raw materials, automobiles and spare parts etc. Enforcement actions in these cases have successfully regulated anticompetitive business practices and contributed to the fostering of a level playing field for market players.

Competition Advocacy

China's anti-monopoly enforcement authorities attach great importance to competition advocacy as a way to raise public awareness of competition law and cultivate a competition culture. Over the past decade, the agencies continuously increased transparency of case information and promoted understanding of typical cases. Meanwhile, emphasis was also placed on anti-monopoly law education and building up of expert panels. More than 3,000 members from government departments, trade associations and various businesses have received relevant training. During the period, the China Competition Policy Forum was held for 7 times while a series of advocacy campaigns were carried out, such as those on the 5th and 10th anniversaries of AML implementation.

The 7th China

Competition Policy Forum With ongoing advocacy initiatives, general understanding of the

anti-monopoly law has increased across the community. Businesses are more aware of the need of compliance while

consumers are more aware of their rights. This is conducive to reaching a consensus on safeguarding the

competition regime and respecting competition rules.

The 7th China

Competition Policy Forum With ongoing advocacy initiatives, general understanding of the

anti-monopoly law has increased across the community. Businesses are more aware of the need of compliance while

consumers are more aware of their rights. This is conducive to reaching a consensus on safeguarding the

competition regime and respecting competition rules.

International Exchange and Collaboration

In response to the globalization of economy and antitrust enforcement, China’s anti-monopoly enforcer made an important move to engage with external counterparts and international communities for cooperation in competition policy and anti-monopoly law enforcement. At present, China has signed 55 cooperation documents in competition policy and anti-monopoly law enforcement with antitrust agencies in 28 countries and regions including the United States, the European Union and Australia. The agency has also engaged in enforcement collaboration with the law enforcers in overseas jurisdictions such as the United States and the European Union on multinational acquisition cases including Dow Chemical acquiring DuPont, Maersk acquiring Hamburg Süd, and Bayer acquiring Monsanto. A dedicated chapter on cooperation in competition policy and anti-monopoly law enforcement has been included in 8 Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) that China signed with Iceland, Switzerland, Australia, Korea, Eurasian Economic Union etc. Further negotiations on competition policy issues for several FTAs are currently underway with the aim of enhancing consistency and integration of international competition rules to safeguard the free flow of trade and investment.

Institutional Reform of Anti-Monopoly Law Enforcement Agencies

Since the AML came into force, three agencies were responsible for law enforcement in China, namely the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) and the former State Administration for Industry and Commerce (former SAIC). These agencies have carried out effective work, but issues such as overlap of functions and enforcement inconsistencies have emerged during the course of law enforcement.

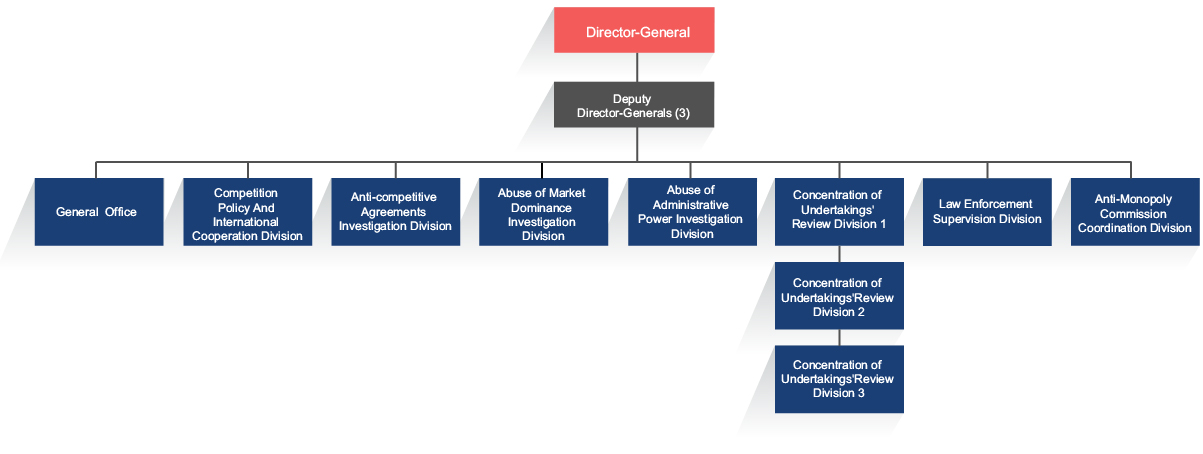

In 2018, China promoted institutional reform of the government and the SAMR has been established to consolidate duties and functions of the former SAIC, price supervision and anti-monopoly law enforcement functions of the NDRC, anti-monopoly law enforcement of the MOFCOM on concentration of undertakings as well as duties and functions of the Anti-Monopoly Commission Office of the State Council. SAMR is now the sole antitrust enforcement agency and undertakes the daily work of the Anti-Monopoly Commission of the State Council. This has solved the problem of function overlaps in the past. According to the Plan for the Institutional Restructuring of the State Council, the Anti-Monopoly Bureau (the Bureau) of the SAMR is specifically responsible for anti-monopoly law enforcement. At present, the institutional reform at the central level has been completed, and the local enforcement agencies’ reform and consolidation are in progress.

The main functions of the Bureau under the SAMR are as follows:

- to coordinate the implementation of competition policies;

- to draft anti-monopoly regulations, regulatory documents and guidelines;

- to enforce the anti-monopoly law, including review of undertaking concentrations, enforcement against restrictions or eliminations of competition through anti-competitive agreements, abuse of market dominance, or abuse of administrative power;

- to provide guidance for enterprises in response to overseas antitrust litigations;

- to handle international cooperation and exchanges on competition policy and anti-monopoly enforcement; and

- to undertake the daily operation of the Anti-Monopoly Commission of the State Council, etc.

The Bureau is headed by the Director-General and three Deputy Director-Generals with an establishment of 41 officers under 10 divisions/offices. The organisation structure is as follows:

From other jurisdictions’ experience in reforming competition law enforcement agencies, the restructuring of institutional functions and departments is only the first step. Substantial consolidation of the functions, officers and rules on law enforcement is even more important. In the past, the NDRC and the former SAIC launched their own rules and regulations separately on areas such as anti-competitive agreements, abuse of market dominance, abuse of administrative power and law enforcement procedures, while some regulations are not consistent; the two bodies also took different modes of empowerment on local enforcement. In this regard, the SAMR has commenced consolidation of the substantive and procedural rules.

On 3 January 2019, the Notice of the State Administration for Market Regulation on the Authority for Anti-Monopoly Law Enforcement was published, by which the provincial enforcement bodies were empowered to enforce the AML in their own administrative regions. The law enforcement authority and jurisdictions of the central and local institutions were further clarified.

In addition, in January 2019, the SAMR successively announced new departmental rules and conducted public consultations in respect of anti-competitive agreements, abuse of administrative powers to eliminate or restrict competition and abuse of market dominance. These rules have consolidated various former documents published by the NDRC and the former SAIC, and set out a unified standard on issues such as factors to consider when determining relevant cases, law enforcement procedures and legal liabilities.

As for the documents signed between the three former agencies and other jurisdictions regarding cooperation on competition policies and anti-monopoly law enforcement, corresponding amendments are also in progress.

Looking Forward

For the anti-monopoly law enforcement agencies in China which have just completed a reform, the year of 2019 will be crucial as rationalization of the enforcement mechanism and integration of the enforcement functions will be carried out. Meanwhile, implementation of competition policies, anti-monopoly law enforcement, international exchanges and cooperation are also major focuses of the Bureau of the SAMR, details of which are as follows:

Firstly, to enhance the implementation mechanism of competition policies: the Bureau will explore competition policy initiatives for free trade zones; conduct research and studies on the implementation of competition neutrality; push forward the amendments of the AML; revise and unify the regulations, regulatory documents and guidelines issued by the three former agencies; launch interpretation and advocacy work on the 4 anti-monopoly guidelines to be released including the Anti-Monopoly Guideline for Automobile Industry; commence assessments of the overall market competition conditions and that of key industries in China; promote development of anti-monopoly databases and commence market competition assessments of industries such as medication, internet and cloud computing.

Secondly, to advance the anti-monopoly law enforcement mechanism: the Bureau will further improve the operation of the Anti-Monopoly Commission and implement its priorities in 2019; improve the law enforcement empowerment mechanism and strengthen guidance on and supervision of local enforcement; provide more training to anti-monopoly enforcers and promote development of a talent pool for law enforcement.

Thirdly, to raise the quality of anti-monopoly law enforcement work: the Bureau will treat all market entities equally, and create a more facilitated and internationalized business environment based on the rule of law; adhere to the regulatory principle of tolerance and prudence; strengthen research efforts on competition issues regarding new economies, new forms of business and new technologies. It will also investigate into significant and typical cases on anti-competitive behaviors and to prevent as well as to regulate; investigate administrative monopolies and break down regional entry barriers; strengthen enforcement efforts in areas concerning people’s livelihood such as public utilities, Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients, construction materials and daily consumer goods.

Fourthly, to deepen international exchanges and cooperation in competition policies and antitrust enforcement: with further exchanges among the three largest antitrust jurisdictions, the Bureau will implement the outcomes of the Sino-European dialogues on competition and the Sino-US top official dialogues; it will also deepen the exchanges with competition agencies in the “Belt and Road” countries and the BRICS countries; duly negotiate and reach agreements on competition policy and enforcement issues in bilateral and multilateral FTAs; make the best use of international cooperation platforms, e.g. the World Trade Organization (WTO), United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTD), Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), for the formation of fair and just international competition rules; provide better guidance to domestic businesses in addressing overseas antitrust disputes.

Anti-Monopoly Law Enforcement in New Economies

New economies brought about by the internet industry are developing rapidly in China. A number of disputes over monopolistic behaviors and concentration of undertakings have taken place in recent years, drawing extensive public attention.

The Bureau pointed out that compared to traditional industries, new forms of businesses such as the internet industry have some obvious features such as dynamic competition, innovation competition and cross-sector competition. First of all, they involve rapid product innovation with actively evolving competitors. Secondly, they begin to cross the boundaries of traditional sectors and new forms of business are emerging continuously. Thirdly, they usually exhibit network effects and “economies of scale” and are therefore likely to form highly concentrated market structures. Fourthly, the market status changes rapidly. Even leading enterprises in the sector may be replaced quickly. New forms of anti-competitive conduct such as algorithmic collusion and algorithmic discrimination are highly covert, thus gathering of evidence is difficult. All of these bring new challenges to anti-monopoly law enforcement.

The Bureau pointed out that it will adhere to the principle of tolerance and prudence for better regulation of competition concerning new economies, such as the internet, according to the law. Firstly, to encourage innovation, the Bureau will adopt a tolerant approach towards new forms of business and create a sound business environment for emerging sectors. Secondly, more stringent enforcement will be undertaken in internet-related areas. Extensive investigation will be carried out into contraventions such as anti-competitive agreements and abuse of market dominance, with the aim of protecting fair market competition and steering online industries towards a healthy and orderly development. Thirdly, new approaches to regulation will be developed from time to time. The Bureau will conduct in-depth studies into internet-related competition issues, draw on overseas experience in legislation and enforcement and introduce innovative enforcement tools and regulation approaches.

Anti-Monopoly Law Enforcement and Competitive Neutrality

According to the definition of the OECD, competitive neutrality aims at providing a level playing field to both state-owned and private businesses. It is framed around eight key areas, including the corporate operation mode, cost identification, commercial rate of return, public service obligations, taxation neutrality, regulatory neutrality, debt neutrality and subsidy control as well as public procurement. As stated clearly in the Plan for Market Regulation during the 13th Five-Year Plan Period announced by the State Council in 2017, it is necessary to reinforce the fundamental status of competition policies and establish a competitively neutral system. In March 2019, Premier Li Keqiang stressed on the Government Work Report that enterprises under all forms of ownership will be treated on an equal footing with respect to access to production factors, market entry license, production and operation, public procurement, tendering and bidding etc.

The SAMR stated that it will centre on the goal of developing a unified national market, ensure a sound competition policy system and adhere to the principle of competitive neutrality in the process of anti-monopoly law enforcement. Firstly, the implementation of the FCRS will be enhanced. It will improve the Detailed Rules for the Implementation of the Fair Competition Review System (for Interim Implementation), implement the Guidance on Third-Party Assessment, carry out studies on supporting rules, such as exclusions and liabilities, and provide a stronger binding effect to the FCRS. Secondly, it will adopt a new regulatory method, improve the effectiveness of its enforcement work and avoid unnecessary interference with the businesses. Thirdly, it will further step up its enforcement efforts. Riding on the consolidation of enforcement agencies, it will optimize the law enforcement mechanism and strengthen enforcement actions; it will investigate into significant and typical monopoly cases as well as disclose typical administrative monopoly cases, and to correct abuses of administrative power that eliminate or restrict competition.

* The interview was conducted in Chinese. The English translation was prepared by the Competition Commission

accordingly.

(Published in May 2019)